This is the most recent result from a long line of research led by Colin Dayan and Mark Peakman, at Cardiff University and King's College London. The goal here is to train the body's immune system not to attack itself, by using either one peptide (in the first trial) or several peptides (in the more recent trial). A peptide is a small part of a protein, and these peptides are part of the insulin molecule. The idea is vaguely similar to

giving people tiny amounts of peanut protein to desensitize them

from peanut allergies. However, it is important to remember that type-1 diabetes

is NOT a classic allergy; the analogy is not perfect, but gives the

general idea.

You can read my summary of the results of the first clinical trial, using one peptide, here:

https://cureresearch4type1diabetes.blogspot.com/2017/11/results-from-phase-i-clinical-trial-of.html

This study was done on adults, within 4 years of diagnosis. This is a little unusual, as most studies either pull from "honeymooners" (within 1 year of diagnosis) or "established" (longer than that). The average time after diagnosis for everyone in this study was about 20 months. So while this study does contain a mix of honeymooners and established T1Ds, there are more people with established T1D.

Here is an image overview of the results. The line with the square is insulin production in the group that got the placebo, while the triangle covers everyone who got the treatment (in three different doses). My summary is two fold: (1) the treated group did better than the untreated group (2) neither group actually got better, it is just that the treated group dropped less than the untreated group.

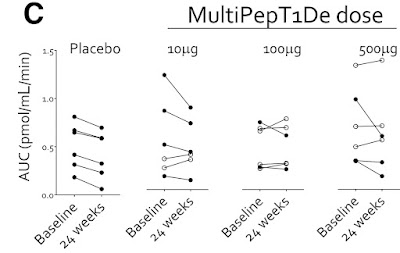

Another way to view the results is this graph:

And notice that in the placebo group, everyone gradually lost C-peptide production during the 6 months of the study. That is what we expect, since people gradually loose insulin production throughout their honeymoon. However, the people who got the smallest dose, two of them actually went up. They were generating more C-peptide after 6 months. The official summery is "Taken together, these findings provide some encouragement for the evaluation of efficacy signals in future, well-powered studies."

Discussion

For myself, I consider C-peptide results to be successful when they go up, and unsuccessful when they go down. Here, the C-peptide results for the treated people went down, so that is disappointing. It is important to see that the study was successful because the treated group generated more C-peptide than the untreated group, and this difference was big enough to be statistically significant. However, both groups (treated and untreated) actually went down in C-peptide production. It is just that the treated group dropped less than the untreated group. So even though this study was scientifically successful, I don't think of the results as successful.

But there is another issue here, which the researchers touched on: "responder vs. non-responder". The overall results in the first chart, the average of everyone who got the treatment and compare this to the average of everyone who did not, and those were the disappointing results. However, the second chart shows all people individually. Certain people got noticeably better, while others did not, or even went down. If you happen to be one of the people who's C-peptide numbers went up, you would be very happy with the results.

So, when evaluating these results should we look at an average of everyone, or focus on specific responders?

It's a complex discussion, too complex to go into here. However, one of the key questions is, do you know ahead of time who will be a responder? Do they share some characteristic or test result, so you know they will be a responder? If so, you can give the treatment only to the responders, and see some big results. If that is the case, the responder result is the important one, and focusing on it is a reasonable thing to do.

However, if you do not know who will respond, or why they respond, then hyping the responder success is just an excuse to exclude data that makes your treatment look bad. In this research, there is no indication of why some people respond and some don't, but the research is still in its early stages. If they do discover why some people respond, while others do not, then suddenly this research could become very valuable to people who are "responders".

Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35073398/

Full Paper: https://diabetesjournals.org/diabetes/article/71/4/722/140961/Immune-and-Metabolic-Effects-of-Antigen-Specific

Clinical Trial Record: https://beta.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02620332

Thanks to ADA's "Diabetes" journal for making this article free, and thanks to all the people who pressured (and continue to pressure) all scientific journals to make these results freely available.

No comments:

Post a Comment